The Eye of the Needle: Textile storytelling with artist Cécile Davidovici

- linda9009

- Aug 22, 2025

- 6 min read

An interview by Linda Falcone

Originally published in

RESTORATION CONVERSATIONS magazine

Come autumn 2025, Paris-based French artist Cécile Davidovici is expected in Florence, where her works will form part of the three-month-long 13-artist exhibition opening at the Museo Sant’Orsola on 5 September 2025. A self-taught embroidery artist with an eye for innovation, Cécile adopts a process that’s both meditative and modern. She is the recipient of an artist production grant, supported by Calliope Arts, in partnership with the museum. The artist shares insights on her 7-year career, from her first approach to needlework, to her collaborative artworks today.

Cécile Davidovici at work during her residency at Museo Sant'Orsola, ph. Claudio Ripalti, courtesy of the museum

Restoration Conversations: You studied theatre in Paris and film in New York, and went on to become an award-winning film writer. Why did you shift your artistic energy from moving pictures to the textile arts?

Cécile Davidovici: I was working as a writer, film director and editor, and first discovered embroidery for fun, as a hobby. The tangible and tactile element of embroidery was a game-changer for me, because it is absent from film, which is more abstract. When I lost my mother twelve years ago, I began to feel that something was missing from my artistic practice. Embroidery gave me the touch I was missing from her. I didn’t mentalise it at the time… I reached that understanding later.

For my first body of works, I drew from VHS-tape home videos from my childhood and explored family themes, where each scene was meant to tell a story. ‘Textile’ and ‘Text’ have the same root texere, which means to weave, so the transition made sense. Telling a story with an embroidered image is a very different exercise than telling it with a series of moving images, but I’m always looking for new ways to evolve, in terms of how I might do it. Today, I am less literal.

RC: You’ve often called embroidery a meditative process. Can you tell us more about your art production from that angle?

CD: Embroidery involves repeating the same gesture over and over again, and as a meditative state, it has helped me. Artistically, I am interested in talking about time – bridges in time between the past and the present and into some sort of eternity, but as I embroider, it is just me in the moment and in a meditative mood. Today, things go so fast; embroidery is a counterpoint. In fact, if I don’t embroider for a few days, I start to feel like I need to, because it brings me a sense of peace. You might call it ‘soft concentration’. The mind stays focused but it’s not strenuous or intense. In a word, I find it a calming practice.

I also feel a real sense of connection by doing something traditionally practiced by women through the ages. It is about escaping, and being with yourself. It is about having time to think, and not being simply overwhelmed by household chores, or being at home but never actually being present. I think that’s what women of the past may have used it for.

RC: Historically, embroidery has been considered one of the ‘minor arts’. How is that preconception changing today and what is your perspective on the difference between craftsmanship and the fine arts?

Embroidery involves repeating the same gesture over and over again, and as a meditative state, it has helped me. Artistically, I am interested in talking about time – bridges in time between the past and the present and into some sort of eternity, but as I embroider, it is just me in the moment and in a meditative mood.

I also feel a real sense of connection by doing something traditionally practiced by women through the ages. It is about escaping, and being with yourself. It is about having time to think, and not being simply overwhelmed by household chores, or being at home but never actually being present. I think that’s what women of the past may have used it for.

It is a media traditionally associated with women, but historically, artistic creation has largely been the domain of men. My aim is to move this craft beyond its conventional links to delicate embroidery or domestic decor, and to redefine it as a powerful form of artistic expression. To be part of this change is incredible, as I help shift embroidery’s standing, by positioning it as a media capable of creating works of art, not craftsmanship. What rings true for any work of art applies to embroidery as well: you have to ask yourself what you are trying to provoke and express. The artisanal nature of needlework is changing. There are so many textile arts. It is about what you want the viewer to feel or to react to, because art is not just about technique, it’s about intention.

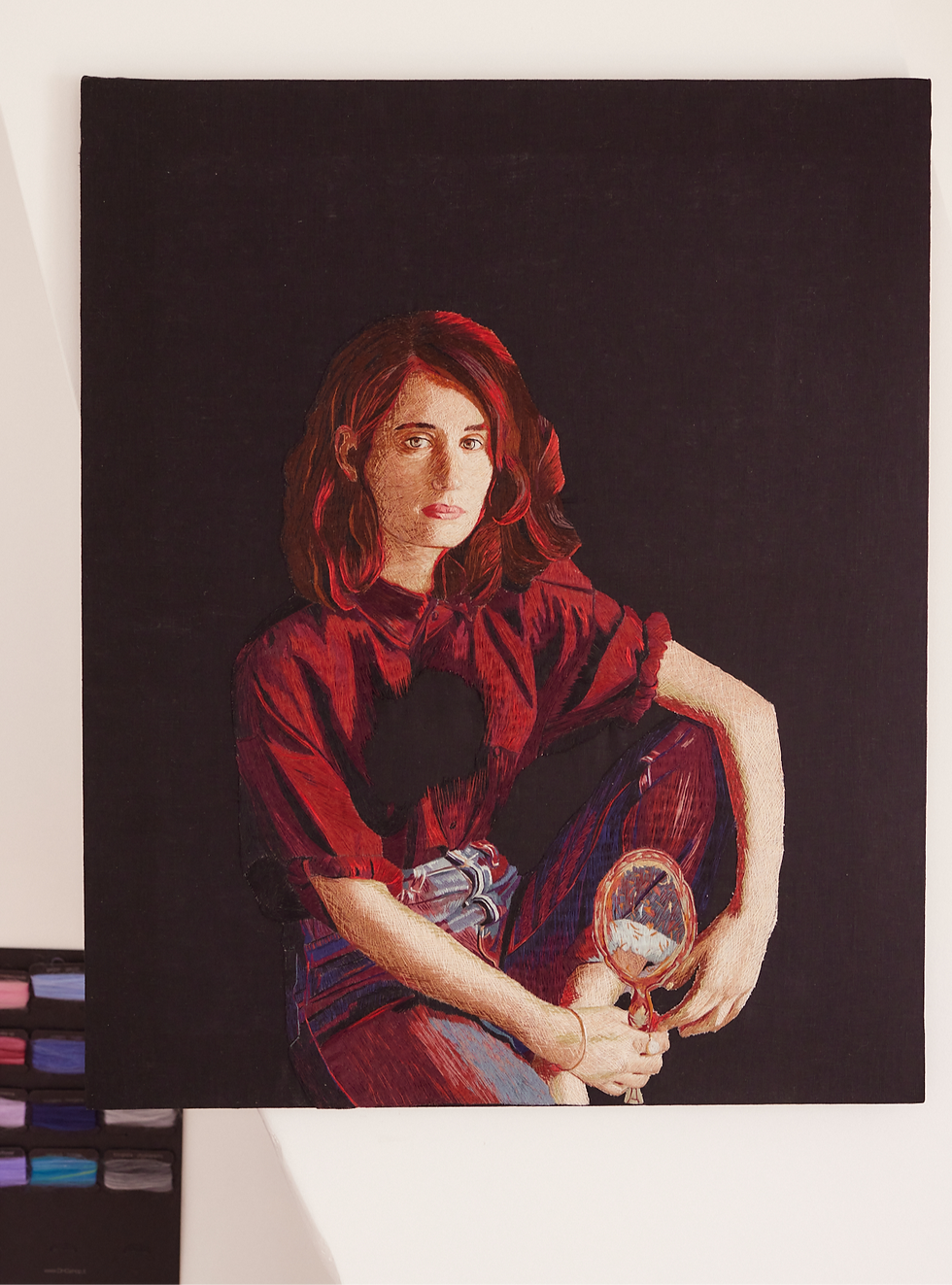

Cécile Davidovici, Portrait of a constant dream IX, 2021

RC: First, let’s start with technique. You’ve brought innovations to your field with a practice you call ‘thread painting’. Tell us more about it.

CD: As the name suggests, thread painting involves using thread to achieve a painterly effect. With needlework, mixing colours is a challenge, because if you try to ‘blend’ threads, you risk getting a ‘hairy’ effect. With painting you can mix or even erase colours, but with thread, it can’t be done, so I’ve managed to achieve a blending effect by using a cross-stitch with thinned thread. For instance, the cotton thread I use is comprised of six strands, and I take it apart and embroider with one strand at a time.

Lighter thread helps me achieve the nuances I’m looking for, which is very important especially with portraits and for flesh tones. The skin has so many colours to interpret and translate, because of how light interacts with it.

The embroidery of my initial works was very dense and thick, and I did not achieve a wide range of hues. Now, I have a wall hosting 500 colours, but I have started dyeing thread – to get more of the shades I am looking for. Five hundred colours sound like a lot, but you need many more in embroidery to attain the versatility of what paint can do.

RC: You mention portraits and the rendering of skin tones. How would you describe your portraiture?

CD: Today – this year – I am doing less portraits, perhaps because people like them so much. I don’t want to get stuck doing just one thing. But I do recognise there’s a sort of magic that happens with portraiture. What I want is for the viewer to look at the portraits I create, and to see themselves. In my dual portraits, both figures represent an alternative version of the same person. The faces are exactly the same, but different, because I can’t embroider the same figure twice. With needlework, even if I try to be exact, there will always be variations, in the colours, in the threads. What a person does with their life is based largely on their heritage, but my dual portraits are a symbol, that you can take different paths, with what you have in hand. I believe portraiture is about transmitting what lies inside us – what we are, and what we carry.

RC: For the Museo Sant’Orsola exhibition, you’ll be working with your partner, French film director and visual artist David Ctiborsky, with whom you’ve created a number of works, including your widely acclaimed still-life or ‘silent life’ series, called La vie silencieuse. What is your collaborative process, and what can we expect at the museum?

CD: We’re preparing two pieces with mixed media – mixed layers imaginary architecture and landscape, that will invite the viewer to walk through time and space as they interact with the pieces. We thought about the concept together. Now David is creating the compositions. Ultimately, we print those images on fabric and I embroider them.. Some parts are completely covered with thread and others remain uncovered, which gives depth to the work. We like the viewer to see the underlying layer, for it to peek through, so you can see how the work was built. David adds to the conversation and enriches my technique by introducing elements of light or shadow to the original image. Our art develops as a constant dialogue. We don’t see our work as two separate phases.

Our research residency last year at Museo Sant’Orsola was a whole new world. Very rarely does an artist have the opportunity to respond to such a huge space – and beyond its size, we’d like to enter into dialogue with its layered landscape, which is still visible. Our two pieces are conceived in order to interact with the place and with each other. One of them is large scale, which is a nice challenge for this technique.

.jpg)

Comments