Carrington: Bloomsbury’s Shooting Star

- Staff

- May 23, 2025

- 7 min read

By MARGIE MACKINNON

This article was first published in Restoration Conversations

Magazine Issue 7, Spring 2025

View of the exhibition, courtesy of Pallant House Gallery

While Vanessa Bell was being celebrated at the MK Gallery, another Bloomsbury figure, Dora Carrington (1893-1932), had her own exhibition at the Pallant House Gallery in Chichester. As in life, Carrington received less attention than the slightly older and better-known Bell. But, as co-curator of the Carrington exhibition Anne Chisholm explains, “we felt that people should be reminded that she was a very gifted and considerable artist. Because she didn’t produce all that many works, and because so many of them had gone missing, her standing as a painter had got a bit sidelined. So, we thought it was high time to have another look.”

Chisholm explains that she first became interested in Carrington while working on a biography of Frances Partridge, who was to become the second wife of Carrington’s husband, Ralph. “Carrington kept attracting my attention,” she says, “but as Frances was my focus, I would have to push her out of the way; but I did find her intriguing. When I was starting work on the biography, I went to see Catherine Carrington, the artist’s sister-in-law, who was then approaching 90 and living in a small cottage near Lewes in Sussex. There, on the wall, was the pencil drawing of Noel, [Catherine’s husband and Dora’s brother]. I thought it was one of the most beautiful drawings I had ever seen. And I still think so.” Done while she was still a student, Noel Carrington (c.1912) shows Carrington’s mastery of the Slade techniques, as taught by drawing master Henry Tonks who was himself profoundly influenced by Michelangelo.

She had been an indifferent pupil at the Bedford School for Girls but her artistic talent had shone through enough for her mother to encourage her move to the Slade, which the older woman imagined as a sort of finishing school for proper young ladies. Carrington, who was only too anxious to shake off her mother’s conventional, petit-bourgeois pretensions and strong religious views, was delighted to find that, in fact, the Slade provided exactly the sort of bohemian environment in which she could re-invent herself. She quickly dropped her first name, which she considered to be redolent of ‘Victorian sentimentality’, and was known thereafter within her circle simply as ‘Carrington’. Defying the conventions of the time, she cut her hair into a short bob, becoming one of the first ‘Cropheads’ (a term coined by Virginia Woolf), along with fellow students Dorothy Brett and Barbara Hiles.

Unlike Bell, whose experience at the Slade was disappointing, Carrington was a star student, winning prizes and scholarships. She was a popular figure with the other young artists, both male and female. “She was,” according to Chisholm, “mesmerising, and people did fall for her tremendously; she had a kind of power to attract.” Her fellow student, Mark Gertler, fell completely under her spell and her failure to reciprocate his passion, Chisholm says, “drove him nearly mad. But, despite their tortured romance, they did have a very strong artistic connection. They were two gifted young painters who helped each other in the early days” and maintained a lifelong friendship.

In the exhibition, Carrington’s 1919 portrait Mrs Box is shown next to Gertler’s 1913 portrait of The Artist’s Mother, which have undeniable similarities in style, composition and subject-matter. Carrington and Gertler were self-proclaimed outsiders, aware that they differed from other members of the Bloomsbury Group in terms of class and educational background. Chisholm notes that, “like many key Bloomsbury people, David Garnett [who would later edit an edition of Carrington’s letters] thought she was socially and intellectually not quite up to them. They were fearful snobs. One of the problems was that her style of painting was very different from that of Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant. And it was Roger Fry and Clive Bell who were the arbiters of Bloomsbury artistic taste.” The 1910 exhibition Manet and the Post-Impressionists, organized by Roger Fry and Clive Bell, was a pivotal event that sparked the Modernist era in British art. “But,” notes Chisholm, “while Carrington attended the exhibition and admired Cezanne and the other French artists in the show, she wasn’t nearly as affected by them as the other Bloomsbury artists were. Her work remained more realistic, with a strong bias towards the representational.”

The most important person in Carrington’s life was one of the Bloomsbury Group’s founders, the writer Lytton Strachey, best known for his biographical study, The Eminent Victorians. They famously met in 1915 at a house party in Sussex given by the Bells where Strachey was a fellow guest. Describing that weekend in a letter to her friend Christine Kuhlenthal, Carrington wrote:

Duncan Grant was there, who is much the nicest of them & Strachey with his yellow face & beard, ug ! We lived in the kitchen & cooked & ate there. All the time I felt one of them would turn into mother & say ‘what breakfast at 10.30! Do use the proper butter knife!’ But no. Everything was behind time. Everyone devoid of table manners, & and the vaguest cooking ensued. Duncan earnestly putting remnants of milk pudding into the stock pot! They were astounded because I knew which part of the leek to cook! What poseurs they are really.

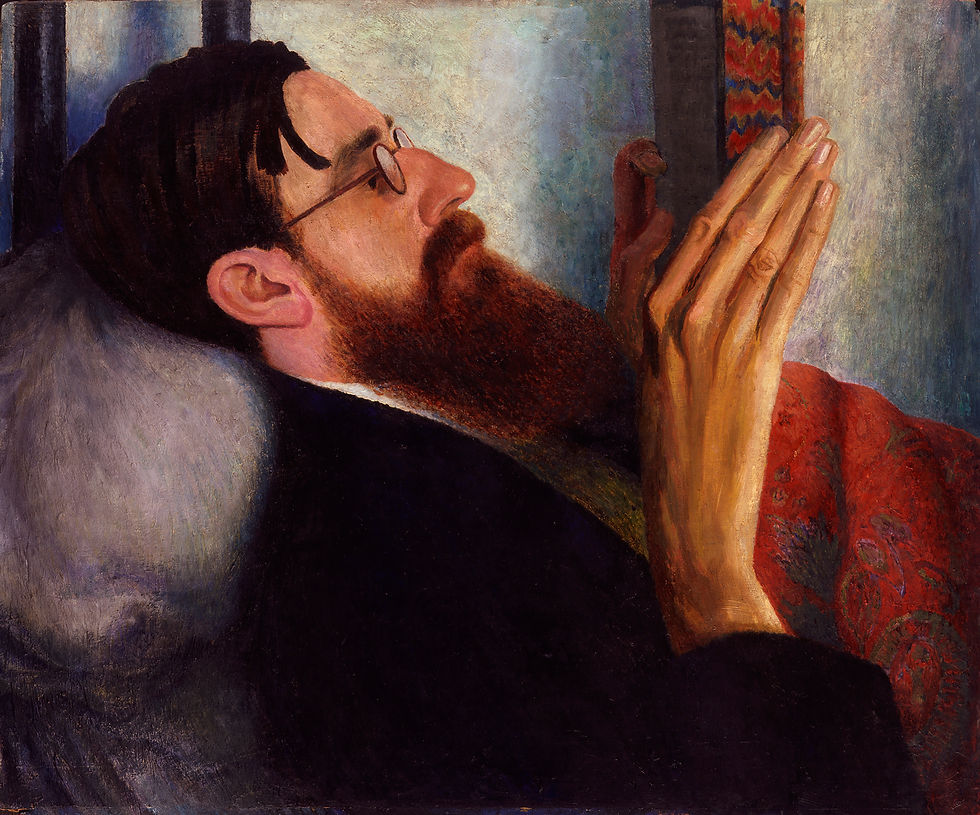

Dora Carrington, Lytton Strachey Reading, 1916 © National Portrait Gallery, London

Carrington at first rebuffed Strachey’s advances only to fall completely and irrevocably in love with him soon afterwards. The fact that he was a well-known homosexual did nothing to dampen her passion. She would eventually go on to marry Ralph Partridge and have affairs with other men and women, but Lytton was the person she chose to spend her life with. Carrington’s Lytton Strachey Reading (1916), which is part of the National Portrait Gallery’s collection, is an intimate and finely observed portrayal that reflects the artist’s deep feelings towards the sitter, while Strachey’s delicate elongated fingers and total absorption in his book identify him as a man of letters.

The artist’s later work defies categorisation. As Chisholm says, “There isn’t necessarily a distinctive Carrington style because she painted in so many different styles. Comparing the Farm at Watendlath (1921) to Spanish Landscape with Mountains (c.1924), for example, you wonder how these could be by the same painter.” The former, a moody English landscape with two tiny enigmatic figures in the foreground, came second only to a David Hockney in a public vote taken in 2014 on the most popular work in British museums. Spanish Landscape, on the other hand, is a surrealistic dreamscape radiating heat from its vivid sensual forms.

Carrington’s artistic output encompassed a wide variety of forms. Even before she had left the Slade, she was commissioned to paint frescoes at Ashridge House, a stately home in Hertfordshire. She was a skillful printmaker, producing four wood-cuts to illustrate Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s first Hogarth Press publication. She worked as a designer at the Omega Workshops, the project established by Roger Fry, Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant to bring modern art into designs for the home. She also designed tiles, cut book plates and painted inn signs. More than anything, she devoted her creative energy to transforming the homes she lived in with Strachey. She painted furniture and created trompe-l’oeil decorations to enhance their shared environment. She was so successful in this that she was showered with requests to embellish friends’ homes as well. A full-size trompe-l’oeil window on an exterior wall at Biddesden House, portraying a maid peeling an apple while the cat beside her looks up at a canary in a cage, can still be seen today. The work was a welcome home present to Diana Guinness (formerly Mitford) after the birth of her son.

Carrington rarely signed or exhibited her works. “She was almost masochistically self-effacing,” says Chisholm. “Her work came from the heart, and she feared exposing too much of herself. She dreaded criticism and not being good enough.” Still, she found a way to earn some money from her art by selling an innovative style of ‘tinsel paintings’. Adapting a Victorian technique of painting on glass, Carrington created her own small works on glass to which she would add foil (which came from cigarette packets and sweet wrappers). After painting the outline of the design onto the back of the glass, she glued on foil within the outlines, adding further paint as necessary to cover the whole surface. Although it was fiddly work, she was able to produce these quirky, luminous pictures quickly and sell them profitably at Fortnum & Mason and other shops. Her small picture of Iris Tree on a Horse (c.1920), “turns a tiny portrait of a friend into a timeless legendary adventure in miniature,” says author Ali Smith. (The picture sold at auction for £10,625 in 2011.)

A much-published photograph shows Carrington cavorting naked on a plinth at Garsington Manor, home of Ottoline and Philip Morrell. She looks directly at the camera and appears to be uninhibited and carefree. In most other photographs, Carrington is either looking away from the camera or peering out shyly from behind her fringe. “She was shy, she was retiring, and then suddenly,” exclaims Chisholm, “she’s naked on a plinth! That is why the woman is so fascinating. You can’t pin her down. You can’t pin her down artistically, sexually or emotionally. She’s quicksilver.”

The Garsington photo was taken in 1917, the year that Carrington and Strachey set up house at Tidmarsh Mill House in Berkshire, possibly the happiest time of her life. After a short illness, Lytton Strachey died in January 1932. Carrington took her own life just a few months later, unable, it seems, to contemplate life without him. She was 38 years old.

No exhibition of her work was held until 1970, thirty-eight years after her death. Until now, her most recent solo exhibition took place at the Barbican in London. Sadly, the budget for that show did not stretch to a catalogue. That absence has been made up for with the Pallant House’s beautiful volume of reproductions of her paintings and decorative objects, along with essays by scholars who have re-examined the significance of her multi-faceted work, and friends whose memories of her convey the deep affection in which she was held.

MARGIE MACKINNON

.jpg)

Comments